Gallery

1 / 22

NGC 3132

The bright star at the center of NGC 3132, while

prominent when viewed by

NASA’s Webb Telescope

in near-infrared light, plays a supporting role in sculpting the surrounding nebula. A

second

star, barely visible at lower left along one of the bright star’s diffraction spikes, is the

nebula’s source. It has ejected at least eight layers of gas and dust over thousands of

years.

But the bright central star visible here has helped “stir” the pot, changing the shape of

this

planetary nebula’s highly intricate rings by creating turbulence. The pair of stars are

locked

in a tight orbit, which leads the dimmer star to spray ejected material in a range of

directions

as they orbit one another, resulting in these jagged rings.

Hundreds of straight, brightly-lit lines pierce through the rings of gas and dust. These

“spotlights” emanate from the bright star and stream through holes in the nebula like

sunlight

through gaps in a cloud.

But not all of the starlight can escape. The density of the central region, set off in teal,

is

reflected by how transparent or opaque it is. Areas that are a deeper teal indicate that the

gas

and dust are denser – and light is unable to break free.

Data from Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) were used to make this extremely detailed

image.

It is teeming with scientific information – and research will begin following its release.

This is not only a crisp image of a planetary nebula – it also shows us objects in the vast

distances of space behind it. The transparent red sections of the planetary nebula – and all

the

areas outside it – are filled with distant galaxies.

Look for the bright angled line at the upper left. It is not starlight – it is a faraway

galaxy

seen edge-on. Distant spirals, of many shapes and colors, also dot the scene. Those that are

farthest away – or very dusty – are small and red.

For a full array of Webb’s first images and spectra, including downloadable files, please

visit:

https://webbtelescope.org/news/first-images

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

2 / 22

NGC 3132

NASA’s Webb Telescope has revealed the cloak of dust

around the second

star, shown at left in red, at the center of the Southern Ring Nebula for the first time. It

is

a hot, dense white dwarf star.

As it transformed into a white dwarf, the star periodically ejected mass – the shells of

material you see here. As if on repeat, it contracted, heated up – and then, unable to push

out

more material, pulsated.

At this stage, it should have shed its last layers. So why is the red star still cloaked in

dust? Was material transferred from its companion? Researchers will begin to pursue answers

soon.

The bluer star at right in this image has also shaped the scene. It helps stir up the

ejected

material. The disk around the stars is also wobbling, shooting out spirals of gas and dust

over

long periods of time. This scene is like witnessing a rotating sprinkler that’s finished

shooting out material in all directions over thousands of years.

Webb captured this scene in mid-infrared light – most of which can only be observed from

space.

Mid-infrared light helps researchers detect objects enshrouded in dust, like the red star.

This Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) image also offers an incredible amount of detail,

including

a cache of distant galaxies in the background. Most of the multi-colored points of light are

galaxies, not stars. Tiny triangles mark the circular edges of stars, including a blue one

within the nebula’s red bottom-most edges, while galaxies look like misshapen circles,

straight

lines, and spirals.

For a full array of Webb’s first images and spectra, including downloadable files, please

visit:

https://webbtelescope.org/news/first-images

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a consortium

of

nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with JPL

and

the University of Arizona.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

3 / 22

SMACS 0723

Thousands of galaxies flood this near-infrared image of

galaxy cluster

SMACS 0723. High-resolution imaging from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope combined with a

natural effect known as gravitational lensing made this finely detailed image possible.

First, focus on the galaxies responsible for the lensing: the bright white elliptical galaxy

at

the center of the image and smaller white galaxies throughout the image. Bound together by

gravity in a galaxy cluster, they are bending the light from galaxies that appear in the

vast

distances behind them. The combined mass of the galaxies and dark matter act as a cosmic

telescope, creating magnified, contorted, and sometimes mirrored images of individual

galaxies.

Clear examples of mirroring are found in the prominent orange arcs to the left and right of

the

brightest cluster galaxy. These are lensed galaxies – each individual galaxy is shown twice

in

one arc. Webb’s image has fully revealed their bright cores, which are filled with stars,

along

with orange star clusters along their edges.

Not all galaxies in this field are mirrored – some are stretched. Others appear scattered by

interactions with other galaxies, leaving trails of stars behind them.

Webb has refined the level of detail we can observe throughout this field. Very diffuse

galaxies

appear like collections of loosely bound dandelion seeds aloft in a breeze. Individual

“pods” of

star formation practically bloom within some of the most distant galaxies – the clearest,

most

detailed views of star clusters in the early universe so far.

One galaxy speckled with star clusters appears near the bottom end of the bright central

star’s

vertical diffraction spike – just to the right of a long orange arc. The long, thin

ladybug-like

galaxy is flecked with pockets of star formation. Draw a line between its “wings” to roughly

match up its star clusters, mirrored top to bottom. Because this galaxy is so magnified and

its

individual star clusters are so crisp, researchers will be able to study it in exquisite

detail,

which wasn’t previously possible for galaxies this distant.

The galaxies in this scene that are farthest away – the tiniest galaxies that are located

well

behind the cluster – look nothing like the spiral and elliptical galaxies observed in the

local

universe. They are much clumpier and more irregular. Webb’s highly detailed image may help

researchers measure the ages and masses of star clusters within these distant galaxies. This

might lead to more accurate models of galaxies that existed at cosmic “spring,” when

galaxies

were sprouting tiny “buds” of new growth, actively interacting and merging, and had yet to

develop into larger spirals. Ultimately, Webb’s upcoming observations will help astronomers

better understand how galaxies form and grow in the early universe.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

For a full array of Webb’s first images and spectra, including downloadable files, please

visit:

https://webbtelescope.org/news/first-images

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

4 / 22

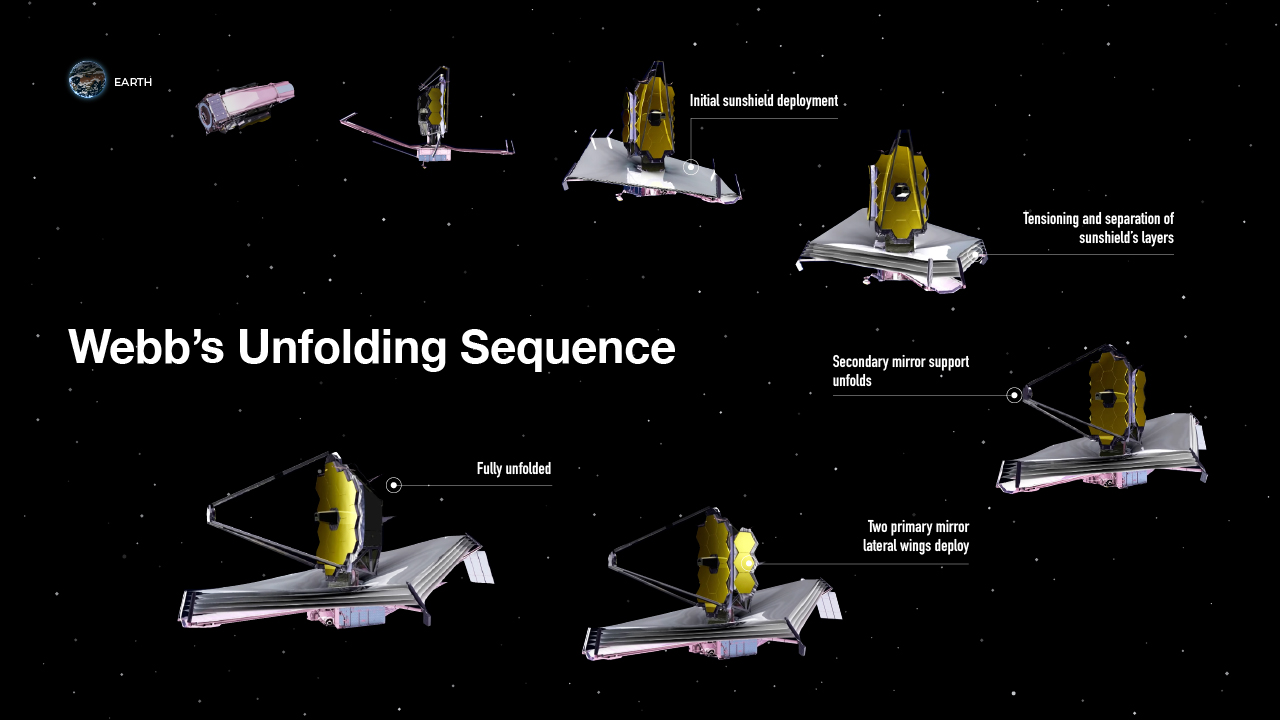

WEBB'S UNFOLDING SEQUENCE

In 2021, Webb was carefully folded up and loaded onto a

ship, which

passed through the Panama Canal on its way to French Guiana in South America, where it

reached

its launch site at the European Spaceport located near Kourou. It is beneficial for launch

sites

to be located near the equator: The spin of the Earth can help give an additional push to

the

rocket.

After launch and during the first month in space, on its way to the second Langrange point

(L2),

Webb undergoes a complex unfolding sequence.

Steps include:

Deploying, tensioning, and separating Webb’s sunshield, a five-layer, diamond-shaped

structure

the size of a tennis court; extending its secondary mirror support structure; and unfolding

its

primary mirror, which has a honeycomb-like pattern of 18 hexagonal, gold-coated mirror

segments.

Deployment and commissioning take time—at least six months. Engineers and scientists

carefully

activate and confirm each and every instrument works properly before the first—but still

unfocused—image of a star field is delivered about two months after launch.

In the fourth month after launch, Webb completes its first orbit around L2—and takes the

first

focused image. This shows that the mirrors are aligned.

After the six-month mark, Webb begins its science mission and starts to conduct routine

science

operations.

Find more detail about the telescope’s size, mirrors, sunshield, orbit, and more.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joyce Kang (STScI)

5 / 22

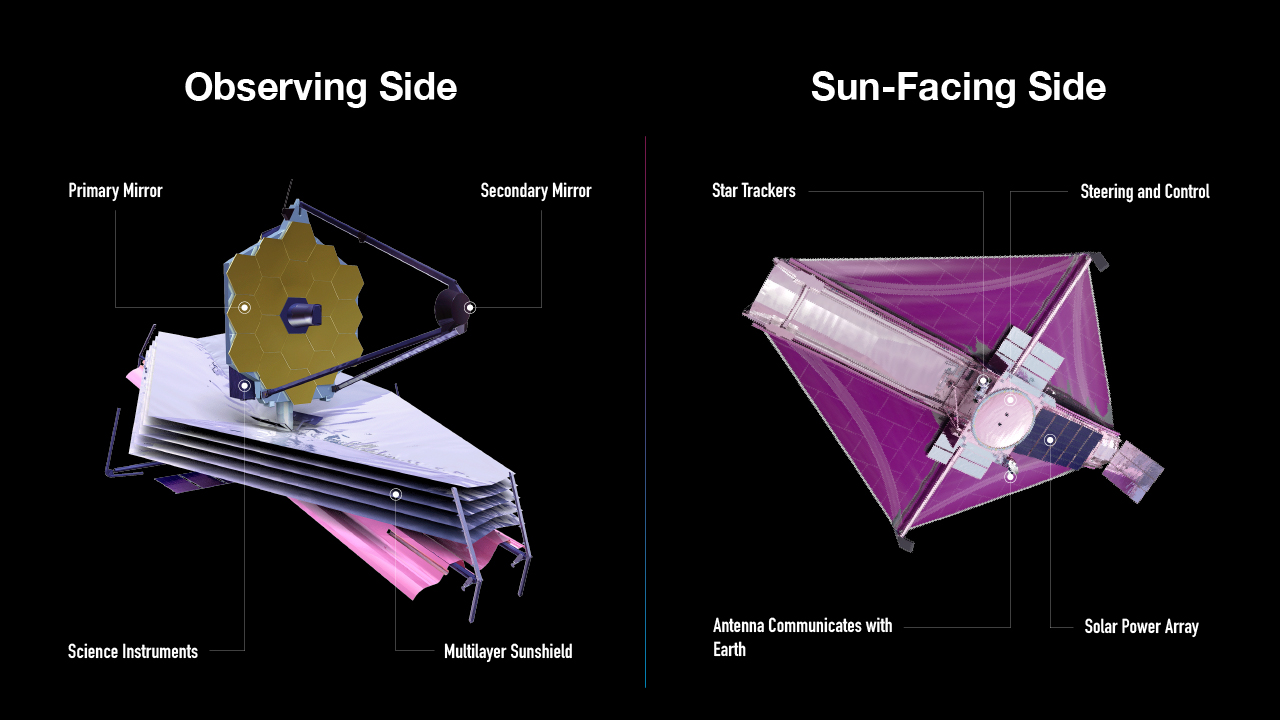

OBSERVING SIDE AND SUN-FACING SIDE

The James Webb Space Telescope has a cool side, which

faces away from the

Sun, and a hot side, which faces the Sun.

Webb’s tennis court-sized sunshield protects the telescope from external sources of light

and

heat, which ensures it can detect faint heat signals from very distant objects. It’s very

important for its observing side to be very, very cold.

The lower part of Webb, where its five-layered sunshield is, faces the Sun. This is where

its

equipment that does not need to be cooled, like its solar panel, antennae, computer,

gyroscopes,

and navigational jets, are.

Webb’s science instruments are housed behind the mirror, separated from the warm

communications

and control technology by the sunshield.

Find more detail about the telescope’s size, mirrors, sunshield, orbit, and more.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joyce Kang (STScI)

6 / 22

L1527

The protostar within the dark cloud L1527, shown in this

image from

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), is embedded within a cloud

of

material feeding its growth. Ejections from the star have cleared out cavities above and

below

it, whose boundaries glow orange and blue in this infrared view. The upper central region

displays bubble-like shapes due to stellar “burps,” or sporadic ejections. Webb also detects

filaments made of molecular hydrogen that has been shocked by past stellar ejections. The

edges

of the cavities at upper left and lower right appear straight, while the boundaries at upper

right and lower left are curved. The region at lower right appears blue, as there’s less

dust

between it and Webb than the orange regions above it.

Credits

SCIENCE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

IMAGE PROCESSING: Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Alyssa Pagan (STScI), Anton M. Koekemoer

(STScI)

7 / 22

WOLF-LUNDMARK-MELOTTE (WLM)

A portion of the dwarf galaxy Wolf–Lundmark–Melotte

(WLM) captured by the

James Webb Space Telescope’s Near-Infrared Camera. The image demonstrates Webb’s remarkable

ability to resolve faint stars outside the Milky Way. Color translation: 0.9-micron light is

shown in blue, 1.5-micron in cyan, 2.5-micron in yellow, and 4.3-micron in red (filters

F090W,

F150W, F250M, and F430M).

Read the story, watch a zoom-in, or explore a side-by-side comparison.

Credits

SCIENCE: NASA, ESA, CSA, Kristen McQuinn (RU)

IMAGE PROCESSING: Zolt G. Levay (STScI)

8 / 22

THE PILLARS OF CREATION

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s mid-infrared view of

the Pillars of

Creation strikes a chilling tone. Thousands of stars that exist in this region disappear –

and

seemingly endless layers of gas and dust become the centerpiece.

The detection of dust by Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) is extremely important – dust

is

a major ingredient for star formation. Many stars are actively forming in these dense

blue-gray

pillars. When knots of gas and dust with sufficient mass form in these regions, they begin

to

collapse under their own gravitational attraction, slowly heat up – and eventually form new

stars.

Although the stars appear missing, they aren’t. Stars typically do not emit much

mid-infrared

light. Instead, they are easiest to detect in ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared light.

In

this MIRI view, two types of stars can be identified. The stars at the end of the thick,

dusty

pillars have recently eroded the material surrounding them. They show up in red because

their

atmospheres are still enshrouded in cloaks of dust. In contrast, blue tones indicate stars

that

are older and have shed most of their gas and dust.

Mid-infrared light also details dense regions of gas and dust. The red region toward the

top,

which forms a delicate V shape, is where the dust is both diffuse and cooler. And although

it

may seem like the scene clears toward the bottom left of this view, the darkest gray areas

are

where densest and coolest regions of dust lie. Notice that there are many fewer stars and no

background galaxies popping into view.

Webb’s mid-infrared data will help researchers determine exactly how much dust is in this

region

– and what it’s made of. These details will make models of the Pillars of Creation far more

precise. Over time, we will begin to more clearly understand how stars form and burst out of

these dusty clouds over millions of years.

Contrast this view with Webb’s near-infrared light image.

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a

consortium of

nationally funded European Institutes (the MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with

JPL and

the University of Arizona.

Credits

SCIENCE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

IMAGE PROCESSING: Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

9 / 22

THE PILLARS OF CREATION

The Pillars of Creation are set off in a kaleidoscope of

color in NASA’s

James Webb Space Telescope’s near-infrared-light view. The pillars look like arches and

spires

rising out of a desert landscape, but are filled with semi-transparent gas and dust, and

ever

changing. This is a region where young stars are forming – or have barely burst from their

dusty

cocoons as they continue to form.

Newly formed stars are the scene-stealers in this Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) image. These

are

the bright red orbs that sometimes appear with eight diffraction spikes. When knots with

sufficient mass form within the pillars, they begin to collapse under their own gravity,

slowly

heat up, and eventually begin shining brightly.

Along the edges of the pillars are wavy lines that look like lava. These are ejections from

stars that are still forming. Young stars periodically shoot out supersonic jets that can

interact within clouds of material, like these thick pillars of gas and dust. This sometimes

also results in bow shocks, which can form wavy patterns like a boat does as it moves

through

water. These young stars are estimated to be only a few hundred thousand years old, and will

continue to form for millions of years.

Although it may appear that near-infrared light has allowed Webb to “pierce through” the

background to reveal great cosmic distances beyond the pillars, the interstellar medium

stands

in the way, like a drawn curtain.

This is also the reason why there are almost no distant galaxies in this view. This

translucent

layer of gas blocks our view of the deeper universe. Plus, dust is lit up by the collective

light from the packed “party” of stars that have burst free from the pillars. It’s like

standing

in a well-lit room looking out a window – the interior light reflects on the pane, obscuring

the

scene outside and, in turn, illuminating the activity at the party inside.

Webb’s new view of the Pillars of Creation will help researchers revamp models of star

formation. By identifying far more precise star populations, along with the quantities of

gas

and dust in the region, they will begin to build a clearer understanding of how stars form

and

burst out of these clouds over millions of years.

The Pillars of Creation is a small region within the vast Eagle Nebula, which lies 6,500

light-years away.

Webb’s NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s

Advanced

Technology Center.

Credits

SCIENCE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

IMAGE PROCESSING: Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Anton M. Koekemoer (STScI), Alyssa Pagan

(STScI)

10 / 22

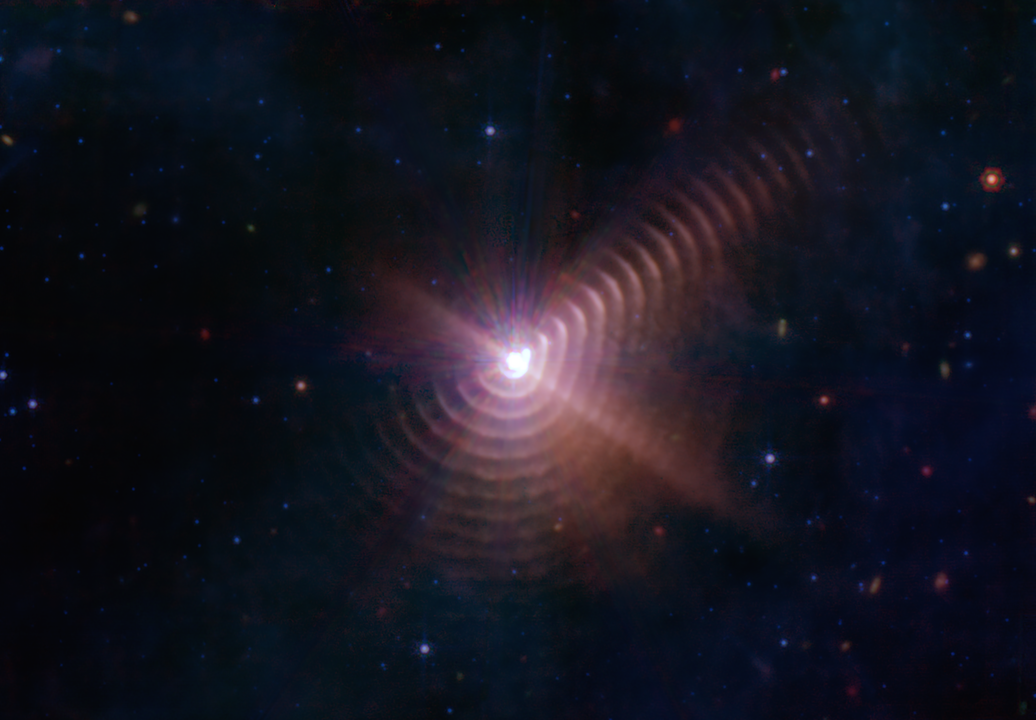

WOLF-RAYET 140

Shells of cosmic dust created by the interaction of

binary stars appear

like tree rings around Wolf-Rayet 140. The remarkable regularity of the shells’ spacing

indicates that they form like clockwork during the stars’ eight-year orbit cycle, when the

two

members of the binary make their closest approach to one another. In this image, blue,

green,

and red were assigned to Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) data at 7.7, 15, and 21

microns

(F770W, F1500W, and F2100W filters, respectively).

Read the story

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, NASA-JPL, Caltech

11 / 22

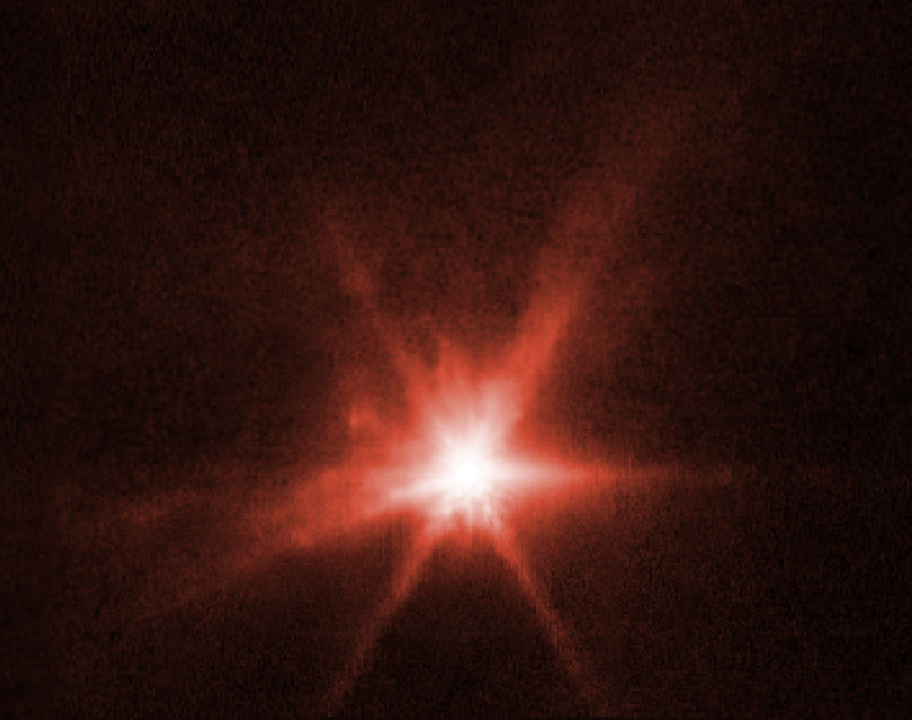

DIMORPHOS

This image from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s

Near-Infrared Camera

(NIRCam) instrument shows Dimorphos, the asteroid moonlet in the double-asteroid system of

Didymos, about 4 hours after NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) made impact. A

tight, compact core and plumes of material appearing as wisps streaming away from the center

of

where the impact took place, are visible in the image. Those sharp points are Webb’s

distinctive

eight diffraction spikes, an artifact of the telescope’s structure.

These observations, when combined with data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, will allow

scientists to gain knowledge about the nature of the surface of Dimorphos, how much material

was

ejected by the collision, and how fast it was ejected.

In the coming months, scientists will use Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) and

Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) to observe ejecta from Dimorphos further. Spectroscopic

data will also provide researchers with insight into the asteroid’s chemical composition.

The observations shown here were conducted in the filter F070W (0.7 microns) and assigned

the

color red.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

Credits

SCIENCE: NASA, ESA, CSA, Cristina Thomas (Northern Arizona University), Ian Wong (NASA-GSFC)

IMAGE PROCESSING: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

12 / 22

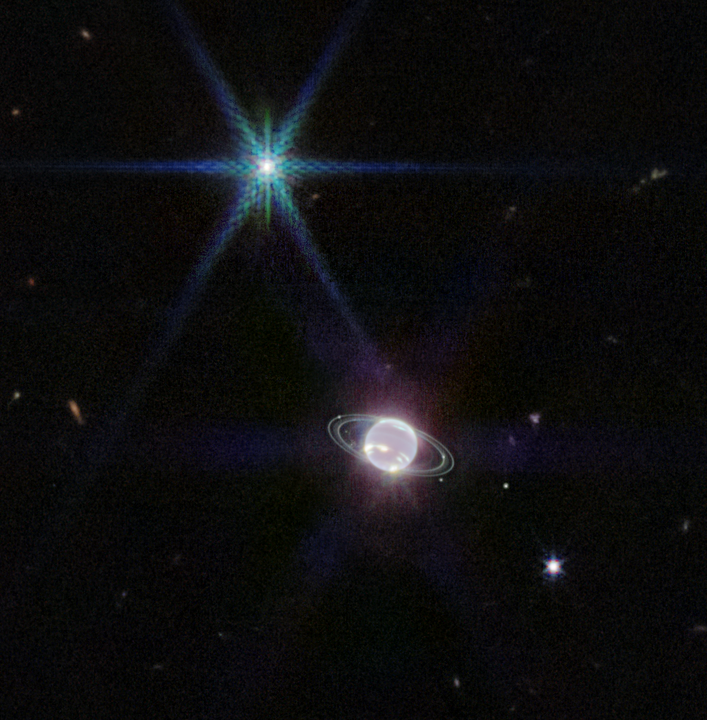

NEPTUNE IN NEAR-INFRARED

This image of the Neptune system, captured by Webb’s

Near-Infrared Camera

(NIRCam), reveals stunning views of the planet’s rings, which have not been seen with this

clarity in more than three decades. Webb’s new image of Neptune also captures details of the

planet’s turbulent, windy atmosphere.

Neptune, an ice giant, has an interior that is much richer in elements heavier than hydrogen

and

helium, like methane, than the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn. Methane appears blue in

visible

wavelengths but, as evident in Webb’s image, that’s not the case in the near-infrared.

Methane so strongly absorbs red and infrared light that the planet is quite dark at

near-infrared wavelengths, except where high-altitude clouds are present. These methane-ice

clouds are prominent in Webb’s image as bright streaks and spots, which reflect sunlight

before

it is absorbed by methane gas.

To the upper left of the planet in this image, one of Neptune’s moons, Triton, also sports

Webb’s distinctive eight diffraction spikes, an artifact of the telescope’s structure. Webb

also

captured 6 more of Neptune’s 14 known moons, along with a smattering of distant galaxies

that

appear as dim splotches and a nearby star.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

IMAGE PROCESSING: Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Naomi Rowe-Gurney (NASA-GSFC)

13 / 22

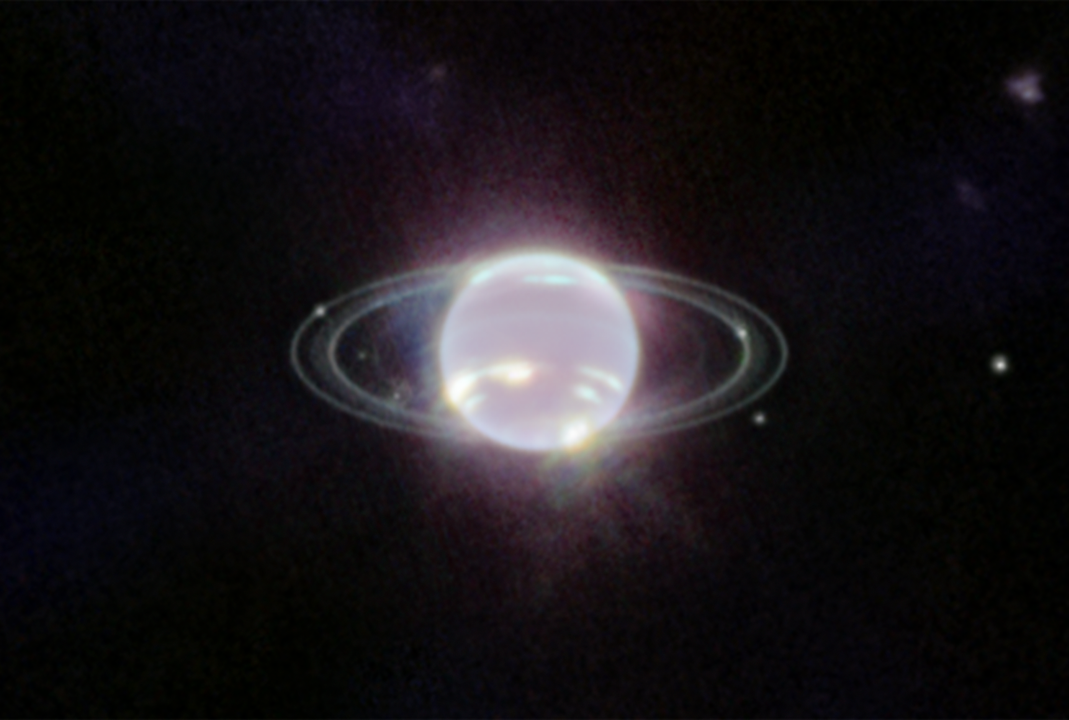

NEPTUNE IN NEAR-INFRARED

Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) image of Neptune,

taken on July 12,

2022, brings the planet’s rings into full focus for the first time in more than three

decades.

The most prominent features of Neptune’s atmosphere in this image are a series of bright

patches

in the planet’s southern hemisphere that represent high-altitude methane-ice clouds. More

subtly, a thin line of brightness circling the planet’s equator could be a visual signature

of

global atmospheric circulation that powers Neptune’s winds and storms. Additionally, for the

first time, Webb has teased out a continuous band of high-latitude clouds surrounding a

previously-known vortex at Neptune’s southern pole.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

IMAGE PROCESSING: Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Naomi Rowe-Gurney (NASA-GSFC)

14 / 22

NEPTUNE AND OTHER GALAXIES IN NEAR-INFRARED

In this image by Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), a

smattering of

hundreds of background galaxies, varying in size and shape, appear alongside the Neptune

system.

Neptune, when compared to Earth, is a big planet. If Earth were the size of a nickel,

Neptune

would be as big as a basketball. In most portraits, the outer planets of our solar system

reflect this otherworldly size. However, Neptune appears relatively small in a wide-field

view

of the vast universe.

Towards the bottom left of this image, a barred spiral galaxy comes into focus. Scientists

say

this particular galaxy, previously unexplored in detail, may be about a billion light-years

away. Spiral galaxies like this are typically dominated by young stars that appear blueish

in

these wavelengths.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

IMAGE PROCESSING: Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Naomi Rowe-Gurney (NASA-GSFC)

15 / 22

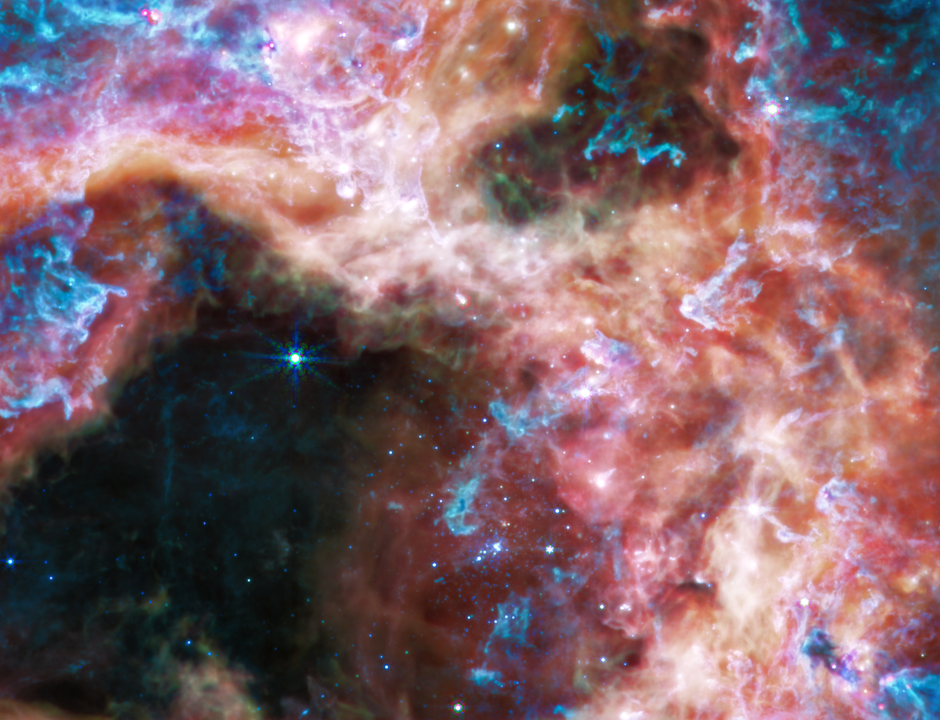

TARANTULA NEBULA (NEAR-INFRARED)

In this mosaic image stretching 340 light-years across,

Webb’s

Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) displays the Tarantula Nebula star-forming region in a new

light,

including tens of thousands of never-before-seen young stars that were previously shrouded

in

cosmic dust. The most active region appears to sparkle with massive young stars, appearing

pale

blue. Scattered among them are still-embedded stars, appearing red, yet to emerge from the

dusty

cocoon of the nebula. NIRCam is able to detect these dust-enshrouded stars thanks to its

unprecedented resolution at near-infrared wavelengths.

To the upper left of the cluster of young stars, and the top of the nebula’s cavity, an

older

star prominently displays NIRCam’s distinctive eight diffraction spikes, an artifact of the

telescope’s structure. Following the top central spike of this star upward, it almost points

to

a distinctive bubble in the cloud. Young stars still surrounded by dusty material are

blowing

this bubble, beginning to carve out their own cavity. Astronomers used two of Webb’s

spectrographs to take a closer look at this region and determine the chemical makeup of the

star

and its surrounding gas. This spectral information will tell astronomers about the age of

the

nebula and how many generations of star birth it has seen.

Farther from the core region of hot young stars, cooler gas takes on a rust color, telling

astronomers that the nebula is rich with complex hydrocarbons. This dense gas is the

material

that will form future stars. As winds from the massive stars sweep away gas and dust, some

of it

will pile up and, with gravity’s help, form new stars.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Webb ERO Production Team

16 / 22

TARANTULA NEBULA (MID-INFRARED)

At the longer wavelengths of light captured by its

Mid-Infrared

Instrument (MIRI), Webb focuses on the area surrounding the central star cluster and unveils

a

very different view of the Tarantula Nebula. In this light, the young hot stars of the

cluster

fade in brilliance, and glowing gas and dust come forward. Abundant hydrocarbons light up

the

surfaces of the dust clouds, shown in blue and purple. Much of the nebula takes on a more

ghostly, diffuse appearance because mid-infrared light is able to show more of what is

happening

deeper inside the clouds. Still-embedded protostars pop into view within their dusty

cocoons,

including a bright group at the very top edge of the image, left of center.

Other areas appear dark, like in the lower-right corner of the image. This indicates the

densest

areas of dust in the nebula, that even mid-infrared wavelengths cannot penetrate. These

could be

the sites of future, or current, star formation.

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a

consortium of

nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with

JPL and

the University of Arizona.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Webb ERO Production Team

17 / 22

CARTWHEEL GALAXY (NIRCam-MIRI)

This image of the Cartwheel and its companion galaxies

is a composite

from Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), which reveals

details that are difficult to see in the individual images alone.

This galaxy formed as the result of a high-speed collision that occurred about 400 million

years

ago. The Cartwheel is composed of two rings, a bright inner ring and a colorful outer ring.

Both

rings expand outward from the center of the collision like shockwaves.

However, despite the impact, much of the character of the large, spiral galaxy that existed

before the collision remains, including its rotating arms. This leads to the “spokes” that

inspired the name of the Cartwheel Galaxy, which are the bright red streaks seen between the

inner and outer rings. These brilliant red hues, located not only throughout the Cartwheel,

but

also the companion spiral galaxy at the top left, are caused by glowing, hydrocarbon-rich

dust.

In this near- and mid-infrared composite image, MIRI data are colored red while NIRCam data

are

colored blue, orange, and yellow. Amidst the red swirls of dust, there are many individual

blue

dots, which represent individual stars or pockets of star formation. NIRCam also defines the

difference between the older star populations and dense dust in the core and the younger

star

populations outside of it.

Webb’s observations capture the Cartwheel in a very transitory stage. The form that the

Cartwheel Galaxy will eventually take, given these two competing forces, is still a mystery.

However, this snapshot provides perspective on what happened to the galaxy in the past and

what

it will do in the future.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a

consortium of

nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with

JPL and

the University of Arizona.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Webb ERO Production Team

18 / 22

CARTWHEEL GALAXY IN MID-INFRARED

This image from Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI)

shows a group of

galaxies, including a large distorted ring-shaped galaxy known as the Cartwheel. The

Cartwheel

Galaxy, located 500 million light-years away in the Sculptor constellation, is composed of a

bright inner ring and an active outer ring. While this outer ring has a lot of star

formation,

the dusty area in between reveals many stars and star clusters.

The mid-infrared light captured by MIRI reveals fine details about these dusty regions and

young

stars within the Cartwheel Galaxy, which are rich in hydrocarbons and other chemical

compounds,

as well as silicate dust, like much of the dust on Earth.

Young stars, many of which are present in the bottom right of the outer ring, energize

surrounding hydrocarbon dust, causing it to glow orange. On the other hand, the clearly

defined

dust between the core and the outer ring, which forms the “spokes” that inspire the galaxy’s

name, is mostly silicate dust.

The smaller spiral galaxy to the upper left of Cartwheel displays much of the same behavior,

showing a large amount of star formation.

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a

consortium of

nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with

JPL and

the University of Arizona.

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Webb ERO Production Team

19 / 22

STAR FORMING IN CARINA NEBULA

What looks much like craggy mountains on a moonlit

evening is actually

the edge of a nearby, young, star-forming region NGC 3324 in the Carina Nebula. Captured in

infrared light by the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope,

this

image reveals previously obscured areas of star birth.

Called the Cosmic Cliffs, the region is actually the edge of a gigantic, gaseous cavity

within

NGC 3324, roughly 7,600 light-years away. The cavernous area has been carved from the nebula

by

the intense ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from extremely massive, hot, young stars

located in the center of the bubble, above the area shown in this image. The high-energy

radiation from these stars is sculpting the nebula’s wall by slowly eroding it away.

NIRCam – with its crisp resolution and unparalleled sensitivity – unveils hundreds of

previously

hidden stars, and even numerous background galaxies. Several prominent features in this

image

are described below.

-- The “steam” that appears to rise from the celestial “mountains” is actually hot, ionized

gas

and hot dust streaming away from the nebula due to intense, ultraviolet radiation.

-- Dramatic pillars rise above the glowing wall of gas, resisting the blistering ultraviolet

radiation from the young stars.

-- Bubbles and cavities are being blown by the intense radiation and stellar winds of

newborn

stars.

-- Protostellar jets and outflows, which appear in gold, shoot from dust-enshrouded, nascent

stars.

-- A “blow-out” erupts at the top-center of the ridge, spewing gas and dust into the

interstellar medium.

-- An unusual “arch” appears, looking like a bent-over cylinder.

This period of very early star formation is difficult to capture because, for an individual

star, it lasts only about 50,000 to 100,000 years – but Webb’s extreme sensitivity and

exquisite

spatial resolution have chronicled this rare event.

Located roughly 7,600 light-years away, NGC 3324 was first catalogued by James Dunlop in

1826.

Visible from the Southern Hemisphere, it is located at the northwest corner of the Carina

Nebula

(NGC 3372), which resides in the constellation Carina. The Carina Nebula is home to the

Keyhole

Nebula and the active, unstable supergiant star called Eta Carinae.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

For a full array of Webb’s first images and spectra, including downloadable files, please

visit:

https://webbtelescope.org/news/first-images

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

20 / 22

STAR FORMING IN CARINA NEBULA

Astronomers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope

combined the

capabilities of the telescope’s two cameras to create a never-before-seen view of a

star-forming

region in the Carina Nebula. Captured in infrared light by the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam)

and

Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), this combined image reveals previously invisible areas of

star

birth.

What looks much like craggy mountains on a moonlit evening is actually the edge of a nearby,

young, star-forming region known as NGC 3324. Called the Cosmic Cliffs, this rim of a

gigantic,

gaseous cavity is roughly 7,600 light-years away.

The cavernous area has been carved from the nebula by the intense ultraviolet radiation and

stellar winds from extremely massive, hot, young stars located in the center of the bubble,

above the area shown in this image. The high-energy radiation from these stars is sculpting

the

nebula’s wall by slowly eroding it away.

NIRCam – with its crisp resolution and unparalleled sensitivity – unveils hundreds of

previously

hidden stars, and even numerous background galaxies. In MIRI’s view, young stars and their

dusty, planet-forming disks shine brightly in the mid-infrared, appearing pink and red. MIRI

reveals structures that are embedded in the dust and uncovers the stellar sources of massive

jets and outflows. With MIRI, the hydrocarbons and other chemical compounds on the surface

of

the ridges glow, giving the appearance of jagged rocks.

Several prominent features in this image are described below.

-- The faint “steam” that appears to rise from the celestial “mountains” is actually hot,

ionized gas and hot dust streaming away from the nebula due to intense, ultraviolet

radiation.

-- Peaks and pillars rise above the glowing wall of gas, resisting the blistering

ultraviolet

radiation from the young stars.

-- Bubbles and cavities are being blown by the intense radiation and stellar winds of

newborn

stars.

-- Protostellar jets and outflows, which appear in gold, shoot from dust-enshrouded, nascent

stars. MIRI uncovers the young, stellar sources producing these features. For example, a

feature

at left that looks like a comet with NIRCam is revealed with MIRI to be one cone of an

outflow

from a dust-enshrouded, newborn star.

-- A “blow-out” erupts at the top-center of the ridge, spewing material into the

interstellar

medium. MIRI sees through the dust to unveil the star responsible for this phenomenon.

-- An unusual “arch,” looking like a bent-over cylinder, appears in all wavelengths shown

here.

This period of very early star formation is difficult to capture because, for an individual

star, it lasts only about 50,000 to 100,000 years – but Webb’s extreme sensitivity and

exquisite

spatial resolution have chronicled this rare event.

NGC 3324 was first catalogued by James Dunlop in 1826. Visible from the Southern Hemisphere,

it

is located at the northwest corner of the Carina Nebula (NGC 3372), which resides in the

constellation Carina. The Carina Nebula is home to the Keyhole Nebula and the active,

unstable

supergiant star called Eta Carinae.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a

consortium of

nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with

JPL and

the University of Arizona.

For a full array of Webb’s first images and spectra, including downloadable files, please

visit:

https://webbtelescope.org/news/first-images

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

21 / 22

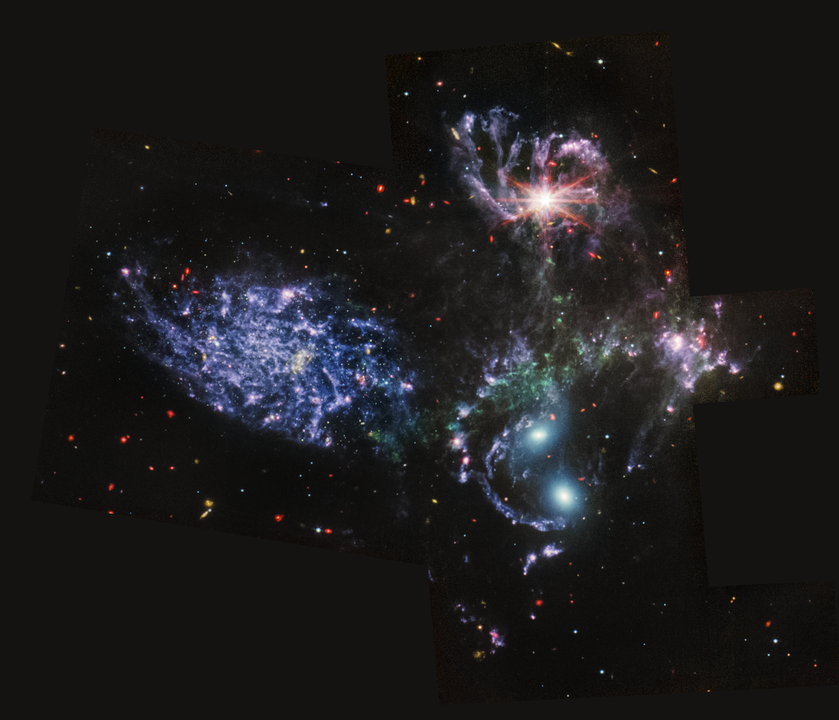

STEPHAN'S QUINTET (NIRCam-MIRI)

An enormous mosaic of Stephan’s Quintet is the largest

image to date from

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, covering about one-fifth of the Moon’s diameter. It

contains

over 150 million pixels and is constructed from almost 1,000 separate image files. The

visual

grouping of five galaxies was captured by Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and

Mid-Infrared

Instrument (MIRI).

With its powerful, infrared vision and extremely high spatial resolution, Webb shows

never-before-seen details in this galaxy group. Sparkling clusters of millions of young

stars

and starburst regions of fresh star birth grace the image. Sweeping tails of gas, dust and

stars

are being pulled from several of the galaxies due to gravitational interactions. Most

dramatically, Webb’s MIRI instrument captures huge shock waves as one of the galaxies, NGC

7318B, smashes through the cluster. These regions surrounding the central pair of galaxies

are

shown in the colors red and gold.

This composite NIRCam-MIRI image uses two of the three MIRI filters to best show and

differentiate the hot dust and structure within the galaxy. MIRI sees a distinct difference

in

color between the dust in the galaxies versus the shock waves between the interacting

galaxies.

The image processing specialists at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore opted

to

highlight that difference by giving MIRI data the distinct yellow and orange colors, in

contrast

to the blue and white colors assigned to stars at NIRCam’s wavelengths.

Together, the five galaxies of Stephan’s Quintet are also known as the Hickson Compact Group

92

(HCG 92). Although called a “quintet,” only four of the galaxies are truly close together

and

caught up in a cosmic dance. The fifth and leftmost galaxy, called NGC 7320, is well in the

foreground compared with the other four. NGC 7320 resides 40 million light-years from Earth,

while the other four galaxies (NGC 7317, NGC 7318A, NGC 7318B, and NGC 7319) are about 290

million light-years away. This is still fairly close in cosmic terms, compared with more

distant

galaxies billions of light-years away. Studying these relatively nearby galaxies helps

scientists better understand structures seen in a much more distant universe.

This proximity provides astronomers a ringside seat for witnessing the merging of and

interactions between galaxies that are so crucial to all of galaxy evolution. Rarely do

scientists see in so much exquisite detail how interacting galaxies trigger star formation

in

each other, and how the gas in these galaxies is being disturbed. Stephan’s Quintet is a

fantastic “laboratory” for studying these processes fundamental to all galaxies.

Tight groups like this may have been more common in the early universe when their

superheated,

infalling material may have fueled very energetic black holes called quasars. Even today,

the

topmost galaxy in the group – NGC 7319 – harbors an active galactic nucleus, a supermassive

black hole that is actively accreting material.

In NGC 7320, the leftmost and closest galaxy in the visual grouping, NIRCam was remarkably

able

to resolve individual stars and even the galaxy’s bright core. Old, dying stars that are

producing dust clearly stand out as red points with NIRCam.

The new information from Webb provides invaluable insights into how galactic interactions

may

have driven galaxy evolution in the early universe.

As a bonus, NIRCam and MIRI revealed a vast sea of many thousands of distant background

galaxies

reminiscent of Hubble’s Deep Fields.

NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced

Technology Center.

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a

consortium of

nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with

JPL and

the University of Arizona.

For a full array of Webb’s first images and spectra, including downloadable files, please

visit:

https://webbtelescope.org/news/first-images

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

22 / 22

STEPHAN'S QUINTET (MIRI)

With its powerful, mid-infrared vision, the Mid-Infrared

Instrument

(MIRI) shows never-before-seen details of Stephan’s Quintet, a visual grouping of five

galaxies.

MIRI pierced through dust-enshrouded regions to reveal huge shock waves and tidal tails, gas

and

stars stripped from the outer regions of the galaxies by interactions. It also unveiled

hidden

areas of star formation. The new information from MIRI provides invaluable insights into how

galactic interactions may have driven galaxy evolution in the early universe.

This image contains one more MIRI filter than was used in the NIRCam-MIRI composite picture.

The

image processing specialists at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore opted to

use

all three MIRI filters and the colors red, green and blue to most clearly differentiate the

galaxy features from each other and the shock waves between the galaxies.

In this image, red denotes dusty, star-forming regions, as well as extremely distant, early

galaxies and galaxies enshrouded in thick dust. Blue point sources show stars or star

clusters

without dust. Diffuse areas of blue indicate dust that has a significant amount of large

hydrocarbon molecules. For small background galaxies scattered throughout the image, the

green

and yellow colors represent more distant, earlier galaxies that are rich in these

hydrocarbons

as well.

Stephan’s Quintet’s topmost galaxy – NGC 7319 – harbors a supermassive black hole 24 million

times the mass of the Sun. It is actively accreting material and puts out light energy

equivalent to 40 billion Suns. MIRI sees through the dust surrounding this black hole to

unveil

the strikingly bright active galactic nucleus.

As a bonus, the deep mid-infrared sensitivity of MIRI revealed a sea of previously

unresolved

background galaxies reminiscent of Hubble’s Deep Fields.

Together, the five galaxies of Stephan’s Quintet are also known as the Hickson Compact Group

92

(HCG 92). Although called a “quintet,” only four of the galaxies are truly close together

and

caught up in a cosmic dance. The fifth and leftmost galaxy, called NGC 7320, is well in the

foreground compared with the other four. NGC 7320 resides 40 million light-years from Earth,

while the other four galaxies (NGC 7317, NGC 7318A, NGC 7318B, and NGC 7319) are about 290

million light-years away. This is still fairly close in cosmic terms, compared with more

distant

galaxies billions of light-years away. Studying these relatively nearby galaxies helps

scientists better understand structures seen in a much more distant universe.

This proximity provides astronomers a ringside seat for witnessing the merging of and

interactions between galaxies that are so crucial to all of galaxy evolution. Rarely do

scientists see in so much exquisite detail how interacting galaxies trigger star formation

in

each other, and how the gas in these galaxies is being disturbed. Stephan’s Quintet is a

fantastic “laboratory” for studying these processes fundamental to all galaxies.

Tight groups like this may have been more common in the early universe when their

superheated,

infalling material may have fueled very energetic black holes called quasars. Even today,

the

topmost galaxy in the group – NGC 7319 – harbors an active galactic nucleus, a supermassive

black hole that is actively pulling in material.

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a

consortium of

nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with

JPL and

the University of Arizona.

For a full array of Webb’s first images and spectra, including downloadable files, please

visit:

https://webbtelescope.org/news/first-images

Credits

IMAGE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI